Banking regulators aren’t usually associated with innovation-friendly policies. But in a notable turn, the U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is moving to establish a new Office of Supervisory Appeals, a change that could reverberate through the world of bank-fintech partnerships. This might sound arcane – an appeals office within a regulator – yet industry insiders and fintech advocates are hailing it as a win for fairness, consistency, and even innovation in financial services. Why? Because it promises an independent avenue for banks to challenge exam findings, potentially tempering the historically cautious (some say overzealous) stance regulators have taken toward banks that partner with fintechs.

Let’s unpack how this bureaucratic reform could improve the climate for bank-fintech relationships, and why it’s seen as a “breath of fresh air” at the FDIC. We’ll also consider the broader regulatory landscape, including concerns about inconsistency and “reputation risk” that have plagued the sector.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Backdrop: Bank-Fintech Tensions

Over the past decade, fintech companies – from online lenders and payment apps to crypto exchanges – have often needed traditional banks to reach customers with regulated services. Many fintechs lack bank charters (which come with federal deposit insurance and the ability to directly hold customer deposits), so they partner with small or mid-sized banks in arrangements sometimes dubbed “Banking as a Service” or, less charitably, “rent-a-bank.” Examples include online lenders that use a bank partner to originate loans nationwide, or neobanks that offer accounts via an underlying FDIC-insured bank.

These partnerships have expanded financial innovation and inclusion (fintechs can rapidly deploy new tech solutions while banks provide the regulatory guardrails). However, they’ve also drawn regulatory scrutiny. Bank regulators worry that some banks might be taking on outsized risks or enabling harmful products via these fintech tie-ups. We saw instances where regulators cracked down on high-interest lending programs run through banks, or expressed concern about how well banks oversee their tech partners.

The FDIC, in particular, under its previous leadership (Chairman Martin Gruenberg, who returned as head in 2022), was perceived as unfriendly to fintech partnerships. In 2023-2024, industry observers noted “heightened scrutiny of bank-fintech partnerships” by the FDIC. Banks received regulatory findings and even enforcement actions related to how they manage third-party fintech relationships. The agency shuttered an internal office (FDiTech) that was meant to engage with fintech innovators, refocusing it purely on internal tech adoption. Congressional Republicans took notice: in February 2024, three House members wrote to the FDIC raising concerns that it was using extralegal pressure to discourage innovation and was not transparent about how examiners treat fintech-related activities.

They pointed out the FDIC’s “troubling history of using extralegal pressures to attain anti-business results” and feared the agency might be quietly throttling fintech partnerships through the exam process. Specifically, they queried how many banks had been subject to orders or “memoranda of understanding” due to fintech partnerships since 2021, and how the FDIC ensures a fair appeals process in such cases. In other words, lawmakers suspected that examiners might be unfairly targeting certain innovative bank activities, with little recourse for the banks.

This is the context in which the American Fintech Council (AFC) – a trade group for fintechs and innovative banks – applauded the FDIC’s new proposal for an independent appeals office. It’s seen as a needed check and balance to ensure that if a bank feels an examiner’s findings (say, “this fintech partnership is unsafe, shut it down”) are unfounded or inconsistent with policy, they can appeal to a neutral body without fear of retaliation.

What the FDIC Is Proposing

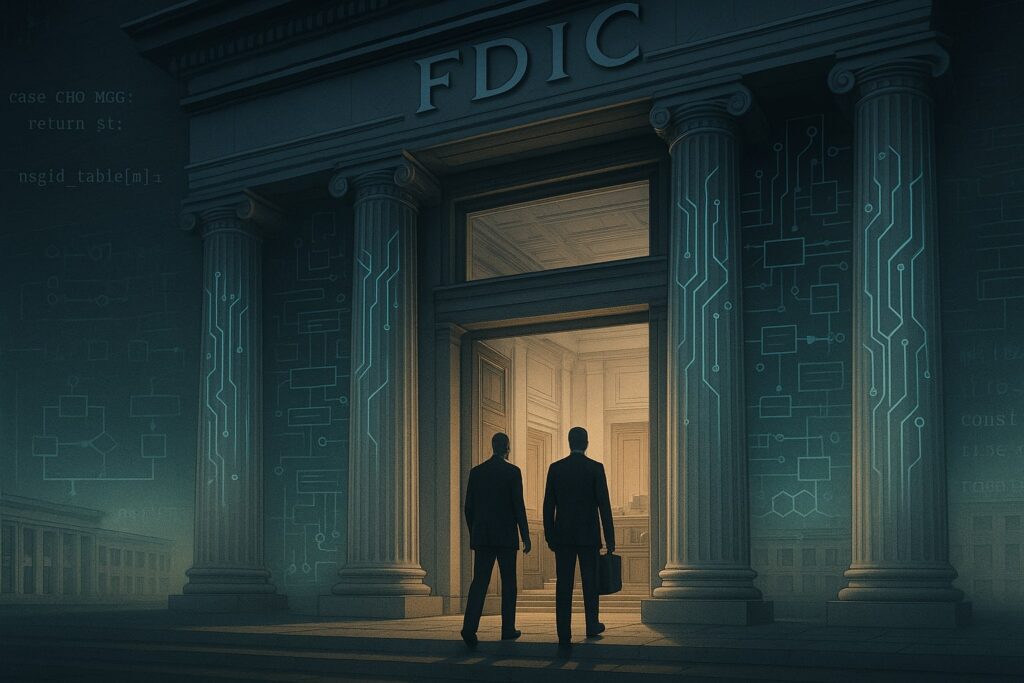

The FDIC’s Board, under Acting Chairman Travis Hill, voted in July 2025 to revive an independent Office of Supervisory Appeals. This isn’t entirely new – a similar office was briefly set up in late 2021 but disbanded in 2022 when leadership changed. Historically, banks could appeal exam decisions to the Supervision Appeals Review Committee (SARC), composed of FDIC board members, but that process was often seen as part of the same hierarchy that made the decisions, and SARC members wore multiple hats.

The new office will be staffed by dedicated officials whose sole job is to hear appeals, not people rotating in from other positions. They will be recruited externally to ensure independence – the idea being they won’t have cozy ties to current examiners or supervisors. They’ll also have term limits to avoid career incentive biases. The office reports directly to the FDIC Chair, giving it clout. In essence, it aims for an “independent, apolitical, and consistent” appeals process.

Phil Goldfeder, CEO of the AFC, praised this move, saying it will ensure decisions are evaluated by “experienced, impartial reviewers” and give institutions a meaningful way to raise concerns. Importantly, the AFC notes it allows appeals “without concern of retaliation”. In the past, banks may have been reluctant to appeal exam findings fearing souring their relationship with their regulator. An independent office makes it safer to say “we think the examiners got this wrong.”

The AFC specifically linked the need for consistency “regardless of an institution’s business model or products”. That’s code for: whether you’re a traditional community bank or one that partners with fintechs on novel products, you should be held to the same clear standards. They’ve felt that innovative banks got more pushback. In fact, Ian Moloney of AFC highlighted how “inconsistent examination practices, especially in the context of innovative financial products, can create unnecessary barriers”. The appeals office can hold examiners to consistent application of rules.

This matters for fintech relationships because much has been subjective. For example, an examiner might cite “reputation risk” – a rather squishy concept – to criticize a bank’s fintech program even if no law is broken. In one era, regulators used reputation risk to pressure banks out of serving certain industries (the notorious “Operation Choke Point” targeted payday lenders, gun shops, etc. via bank pressure). Fintechs worried similar subjective reasoning was being applied to them.

Indeed, in March 2025, Acting Chair Hill told Congress the FDIC would eliminate “reputation risk” as a formal basis for supervisory actions. He acknowledged criticisms that this concept had been used to discourage banks from lawful but politically sensitive businesses. The FDIC plans a rule so examiners “do not issue supervisory findings based solely on reputational factors”. This is a significant policy shift. It mirrors the OCC (another regulator) which did the same. For bank-fintech ties, it means an examiner can’t just say “we don’t like that you’re dealing with crypto exchanges because it might look bad” without citing tangible risk factors. They must focus on compliance, credit risk, operational risk – not vague image concerns.

Combine this with the appeals office, and you see a pattern: the FDIC under new leadership is consciously pulling back on what industry saw as overreach. Hill seems intent on reducing impediments to innovation while maintaining safety and soundness. A Global Financial Regulation blog noted that the FDIC wants to stick to its core mandate and “reduce impediments to fintech, innovation, mergers, bank formation, and efficient supervision”. That’s a mouthful, but basically it suggests a more open-door approach.

Impact on Bank-Fintech Dynamics

All these changes – appeals, curbing reputational risk, etc. – could have a salutary effect on bank-fintech partnerships:

- Greater Confidence for Banks: Some banks have been wary of partnering with fintechs out of fear regulators will hammer them. If banks know they can appeal an unfair exam ruling, they may be bolder in exploring partnerships. Also, removal of reputation risk as a catch-all means if they do proper due diligence and risk management with a fintech, they shouldn’t be arbitrarily penalized. The appeals mechanism will enforce that regulators follow the actual rules and guidance, not personal biases.

- Consistency Across Regions: A complaint was that different FDIC regions or exam teams took different stances. One bank might get scolded for something that another bank’s examiner is fine with. With an appeals office ensuring “consistent application of supervisory standards”, banks and fintechs can expect more uniform treatment. This levels the playing field. It also helps innovative banks because they won’t be subject to a “luck of the draw” on examiner attitudes. Consistency breeds predictability, which is crucial for business planning.

- Encouraging Responsible Innovation: The AFC uses the term “responsible innovation” repeatedly. They want banks to innovate but within guardrails. The appeals process doesn’t give banks a free pass to do risky things; it just ensures that if a bank is operating within the rules, it won’t get slapped down due to novelty alone. Thus, the good actors – banks truly committed to compliance while partnering with fintechs – will feel supported. The bad actors or poorly managed programs will still face scrutiny (and rightly so), but now there’s clarity on what the real issues are.

- Faster Resolution of Disputes: If a bank believes an examiner’s finding is wrong, historically it might languish in internal discussions or informal appeals for a long time, possibly hampering the business meanwhile. A dedicated office can more quickly adjudicate disputes. That agility means fewer opportunities lost. For example, if an examiner tells a bank to halt a fintech program pending some changes, and the bank thinks that’s excessive, an appeal could overturn or modify that decision faster, allowing the program to continue with minimal interruption (or confirming it needs adjustment, but at least the uncertainty is resolved).

- Transparency and Accountability: The FDIC plans to publish guidelines and likely results of appeals (anonymized). This sets precedents. Over time, that can clarify grey areas. Maybe one appeal establishes how much due diligence a bank must do on a fintech partner – if clearly delineated, all banks can follow that and avoid disputes. Essentially, the appeals outcomes could form a body of case law for bank supervision. That is far more transparent than backroom negotiations. Regulators themselves will have to ensure their examiners are reasonable lest they get frequently overturned, which would be embarrassing. So it nudges the whole supervisory process toward clearer, more defensible positions.

The fintech industry is celebrating this (AFC’s glowing press release is evidence). They even reference their support of the FAIR Exams Act in Congress which would codify some of these concepts across regulators. It’s bipartisan momentum recognizing that regulators should be tough but fair, and not capricious. The ultimate beneficiary, one can argue, is the consumer. Why? Because a fairer supervisory environment means more innovation can flourish, leading to better financial products – as long as they’re safe. Conversely, in an overzealous regime, banks might avoid offering, say, a small-dollar loan via a fintech that could help consumers, for fear of examiner disapproval. Balanced oversight could unleash more responsible products to market.

Caution: Will It Work?

Of course, one has to ask: Will banks actually use the appeals process, and will it truly be independent? The FDIC tried this in 2021 and it was scrapped by the next Chair. That hints at regulatory whiplash: changes in leadership can reverse policy. But the fact that the FDIC Board’s July 2025 vote was unanimous suggests broad support, possibly insulating it from immediate reversal. If codified by legislation (the FAIR Act), it would be even sturdier.

Banks might still be cautious initially in filing appeals until they see evidence of fairness. But the AFC’s endorsement will embolden them. Trade groups don’t publicly push something unless members are prepared to use it. We might see test cases soon: a bank could appeal a Matter Requiring Attention (MRA) or similar finding about a fintech partnership, and that case will set the tone.

It’s also key that the FDIC concurrently addresses examiner behavior. The removal of reputational risk criteria is a big one. Also, Hill’s FDIC is re-examining earlier policies like the one requiring banks to pre-notify the FDIC before engaging in crypto activities. They found that approach heavy-handed and are working on a clearer framework that defines acceptable crypto activities with sound risk management. This indicates a shift from a stance of “ask us for permission and we might say no” to “here are the rules, follow them and you can proceed.” That philosophical change, combined with appeals, really does reduce friction for banks experimenting with new tech (crypto being a prime example).

From the fintech perspective, their bank partners are their lifeblood (for deposits, lending licenses, etc.). If those banks are less nervous about regulatory backlash, fintechs gain more willing partners. That could revive some partnership deals that were on ice. Recently, some banks curtailed certain fintech programs (like issuing loans for fintechs) after regulators signaled concern. For instance, in 2023 the OCC and others warned about certain “rent-a-charter” lending models. Banks pulled back. With clearer guidelines and an appeals safety valve, banks might re-enter those partnerships with proper safeguards, giving fintechs a second chance to prove themselves.

One real-life implication: new charters and mergers. The globalfinreg blog line suggests the FDIC wants to ease bank formation. Fintechs have tried to obtain bank charters (remember Varo got one, others like SoFi got one via merger, many have applied). The FDIC under Gruenberg was perceived to slow-roll new charters, especially if fintech-y. A more open FDIC could accelerate approvals for fintech-related banks or industrial loan companies (ILCs) which tech firms have pursued. The appeals office itself doesn’t directly do that, but it’s part of an ethos of openness.

We should temper enthusiasm: regulators will still rightly scrutinize high-risk ventures. If a bank-fintech partnership is leading to consumer harm (e.g., a fintech’s app is causing lots of errors, customers losing money), the FDIC examiners will act, and appeals likely won’t save a bank that truly messed up. The goal is not to let banks off the hook, but to ensure they’re judged on real risk and rule compliance, not subjective or inconsistent factors.

One can draw a parallel to a judicial system: by giving banks a kind of “court of appeals,” the regulatory ecosystem acknowledges that examiners (like trial judges) can make mistakes or have biases, and a higher review is healthy. Historically, banks have had an uneasy relationship with their regulators – there’s a power imbalance since regulators can effectively make or break a bank’s business decisions. Restoring some balance could improve trust on both sides. Examiners might also be more careful and thorough, knowing their decisions could be second-guessed by an independent panel.

The timing is also notable. 2025 has a new political climate (post-2024 election with a different administration perhaps? Actually as of mid-2025, still Biden admin but Trump re-election attempt in background; however, FDIC’s changes seem internally driven by a Republican-appointed acting chair). Regardless of politics, there’s recognition that innovation in banking is crucial (to compete with foreign tech, to include the unbanked, etc.), and regulators must modernize. The Fed and OCC have their own innovation efforts; the FDIC making these moves signals regulators don’t want to be seen as stifling fintech.

Conclusion: A Fairer Playing Field for Innovators

In sum, the FDIC’s Office of Supervisory Appeals could be a game-changer in the minutiae of bank regulation that ultimately shapes how banks and fintechs collaborate. It may bring due process to bank exams, encouraging responsible innovation by assuring banks that if they play by the rules, they won’t be capriciously punished. As the American Fintech Council put it, this reform “restores trust in the process” for regulators and institutions alike.

For fintech companies, that means more doors open at banks willing to partner, more consistency in how their partnerships are viewed by regulators, and fewer abrupt disruptions due to examiner whims. It’s telling that this relatively small bureaucratic tweak has fintech folks cheering – it underscores how much regulatory uncertainty has been a thorn in the side of fintech expansion.

There are certainly broader issues to tackle: crafting clear guidance for bank-fintech partnerships (the agencies did issue some guidance on third-party risk in 2023), updating rules to accommodate fintech models, and ensuring consumer protection in new tech-driven services. But an impartial appeals process and elimination of fuzzy “reputation” critiques go a long way to addressing the fear that innovation will be squashed not by law, but by opaque oversight. Transparency and consistency are fundamentally pro-innovation because they allow experimentation within known boundaries.

We’ll know the Office of Supervisory Appeals is working if, in a year or two, we hear of banks actually citing successful appeals or at least feeling empowered. Also, if industry anecdotes of “examiner X said we can’t do this because it’s new” start fading. In an ideal world, appeals won’t be needed often – their existence will itself ensure examiners are reasonable. As Travis Hill noted, a robust appeals process even helps make sure exam policies are applied uniformly across the country. That could iron out regional differences and ensure fintech-forward banks in, say, one state aren’t at disadvantage to those in another.

This development is one of those inside-baseball regulatory changes that doesn’t grab headlines like a new fintech IPO might, but its impact on the plumbing of innovation is significant. It shows regulators adjusting to the new financial ecosystem where banks and fintechs are intertwined. If successful, it fosters a more collaborative relationship – regulators become partners in ensuring safety and progress, rather than being seen as roadblocks. As a result, consumers and small businesses could see more innovative financial products available, with confidence that both the bank and regulator are on board.

In the end, a healthy bank-fintech partnership landscape requires both innovation and oversight. The FDIC’s moves suggest that oversight can be done in a smarter, fairer way that doesn’t throw cold water on innovation. That’s a positive sign for the fintech sector and for the evolution of the banking industry into the digital age.