It’s not often that a crypto innovation gets mentioned in the same breath as U.S. government debt management, but stablecoins are rapidly forging that connection. Digital dollars like USDT (Tether) and USDC (Circle) have quietly become major buyers of U.S. Treasury bills – so much so that they now rank among the world’s largest non-sovereign holders of American debt. Lawmakers have taken note. A new bipartisan proposal – the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins (GENIUS) Act – aims to formalize how these dollar-pegged tokens operate. And in doing so, it could supercharge the demand for U.S. Treasurys by institutionalizing stablecoin reserve structures in unprecedented ways.

In our earlier coverage of the GENIUS Act, we explored how Congress is moving to finally regulate stablecoins and bring them into the mainstream financial fold. Now, as a follow-up, let’s dive deeper into a surprising implication of that move: stablecoins may soon become one of Uncle Sam’s best friends in the Treasury market. By mandating 100% reserve backing in safe assets, the GENIUS Act would effectively turn every major stablecoin issuer into an avid buyer of short-term U.S. government debt – turbocharging demand for Treasury bills and reshaping parts of the financial landscape in the process.

Table of Contents

ToggleFrom Crypto Niche to Major Treasury Holder

To understand the magnitude of what’s unfolding, consider this startling fact: stablecoin issuers are already the world’s 18th largest holders of U.S. government debt. According to data tracked by Tagus Capital, companies like Tether and Circle collectively hold over $120 billion in U.S. Treasury securities. That puts these private crypto firms ahead of entire countries like Germany and South Korea in terms of U.S. debt ownership. In mid-2024, Tether – issuer of the largest dollar stablecoin, USDT – alone held about $91 billion in U.S. Treasurys, while Circle’s USDC reserve accounted for another $29 billion in short-term U.S. debt and repo agreements.

Those numbers, remarkable as they are, have largely accumulated without a formal regulatory framework. Stablecoin issuers until now have operated in a gray area – adhering to a patchwork of state licenses and self-imposed standards – but they’ve still ended up plowing tens of billions into U.S. Treasurys as backing for their digital dollars. USDT and USDC, intended to maintain a 1:1 peg with the U.S. dollar, achieve their stability by holding high-quality liquid assets in reserve. In practice, that means enormous portfolios of Treasury bills, cash, and overnight loans secured by Treasurys. For perspective, stablecoin reserves have become so large that Senator Bill Hagerty – lead sponsor of the GENIUS Act – explicitly highlighted “driving demand for U.S. Treasuries” as one of the key benefits of embracing stablecoin innovation. It’s a striking alignment of incentives: crypto-dollar issuers want safe yield and liquidity, and the U.S. government needs steady buyers for its debt.

Locking In 100% Reserves: The GENIUS Act’s Big Promise

What the GENIUS Act does is take this ad hoc reality and turn it into law. Every payment stablecoin would be required to maintain 100% reserves in high-quality, liquid assets. In plain English, if you issue a U.S. dollar-pegged token under this law, you must have the equivalent value sitting in cash, 3-month Treasury bills, or similarly liquid instruments at all times. No ifs, ands, or buts – every token in circulation needs a corresponding dollar or T-bill in the vault. This is designed to “squash fears of a run or de-pegging event” by ensuring stablecoins are fully redeemable on demand. It’s a stringent rule, but one that legitimate issuers like Circle have already been following voluntarily. Now it will become the industry-wide standard, enforced by regulators.

Crucially, the Act also mandates transparency: issuers must publicly disclose their reserve composition each month, and any stablecoin with over $50 billion in circulation must provide annual audited financial. In short, no more mystery about what’s backing your stablecoin. This responds to past controversies – for instance, Tether’s long-running opacity and the skepticism it faced about its reserves. Under GENIUS, whether you’re a crypto startup or a Wall Street titan, if you issue a “payment stablecoin,” you’ll have to open your books and prove the dollars or T-bills are there. By institutionalizing this 100% backing and audit regime, the law essentially cements stablecoins as a new kind of narrow bank – entities that take in funds and park them entirely in safe assets.

For the U.S. Treasury market, this is music to the ears. It means that every additional $1 of stablecoin issued translates to an additional $1 invested in Treasurys or Fed-approved equivalents. Stablecoin growth and Treasury demand become two sides of the same coin. The reserve rules will channel potentially massive rivers of cash into short-term government debt – primarily Treasury bills in the sub-3-month range, since issuers must manage interest rate risk and keep assets ultra-liquid. Indeed, the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee noted that proposed stablecoin legislation would likely require issuers to hold mostly <93-day T-bills, concentrating their holdings on the front end of the yield curve. In effect, stablecoins could become regular, predictable buyers of 3-month T-bills, rolling them over continuously as tokens circulate.

The GENIUS Act doesn’t stop at just backing requirements. It also imposes risk-management rules to prevent stablecoin issuers from straying into dangerous territory. Issuers will have to diversify reserves (no putting all eggs in one basket), match assets and liabilities to manage interest rate swings, and even maintain capital buffers and liquidity akin to bank standards. The clear intent is to avoid any scenario where a stablecoin “breaks the buck” – similar to how a money market fund breaking $1 value can trigger panic. Congress is effectively asking stablecoin issuers to behave like ultra-conservative banks, with oversight ensuring they don’t, say, load up on long-term bonds that could crash in value if rates rise. By keeping issuers on a short leash, the law aims to make stablecoins as safe as the dollars in your wallet – and by extension, further entwine these tokens with the stability of U.S. government debt itself.

The Scale of What Could Come: From Billions to Trillions

All of this raises a big question: just how much might stablecoin-related Treasury demand grow if the GENIUS Act passes? Today’s ~$120 billion in Treasurys held by stablecoin issuers could be just the tip of the iceberg. With regulatory clarity, a whole host of new players – from major fintech firms to traditional banks and perhaps even tech giants – could enter the stablecoin arena. Senator Cynthia Lummis underscored this point, arguing that a bipartisan framework for stablecoins is “critical to maintaining the U.S.’s dollar dominance and promoting responsible financial innovation”. In other words, Congress is inviting more competition and innovation in the stablecoin space, not less. The Act explicitly allows non-bank companies (including Big Tech or startups) to issue stablecoins under federal oversight, so long as they play by the rules. This inclusive approach means we might soon see not just Circle and Tether, but perhaps PayPal, JPMorgan, fintech unicorns, or even an Amazon or Google-branded stablecoin, all vying to provide digital dollars for payments and commerce.

If that happens, the size of the stablecoin market could explode. Analysts at Citi recently projected that stablecoin supply could reach $1.6 trillion by 2030 in their base-case scenario – and in a bullish scenario, as high as $3.7 trillion. Even Boston Consulting Group has forecast around $2.4 trillion by 2030. For context, the current total outstanding stablecoin supply (mostly USD-backed) is on the order of a few hundred billion. So we’re talking about a potential tenfold or more increase in the coming years if stablecoins truly go mainstream. Another estimate cited by U.S. Treasury advisors posits that evolving market dynamics could accelerate stablecoins to around $2 trillion by 2028 – a number that would have seemed fantastical just a couple years ago. But with 2025 shaping up as the year stablecoins gain mainstream legitimacy, these big numbers start to look plausible.

What do those trillions mean for Treasury demand? Quite simply, every additional stablecoin dollar would mean another dollar invested in U.S. Treasurys or equivalent safe assets. David Sacks, the White House’s crypto czar, recently pointed out the enticing upside for government finance: “Stablecoins have the potential to ensure American dollar dominance internationally…and in the process create potentially trillions of dollars of demand for US Treasuries, which could lower long-term interest rates”. Trillions in new demand is not hyperbole when you consider those market-size forecasts. If, say, $2 trillion in stablecoins materializes by late this decade and is fully backed by T-bills, that would exceed the current foreign holdings of Treasurys by even the largest U.S. creditors. (Japan and China each hold roughly $0.8–$1.1 trillion in U.S. Treasurys today, for comparison.) It’s as if a new “country” of stablecoin issuers rose up to become one of the top owners of U.S. debt – except in this case, that country is a loose network of fintech firms and trust companies, marshaling funds from users around the globe who want digital dollars.

Of course, such growth isn’t automatic or guaranteed. It will depend on real demand for stablecoins in everyday commerce and finance. But regulatory clarity is a catalyst. With the GENIUS Act, a PayPal or Coinbase can expand stablecoin offerings with confidence, community banks can explore issuing tokens for local customers, and institutional players might green-light projects that were on hold due to legal uncertainty. Even U.S. banks could join in more directly; under the Act’s dual framework, insured banks can issue stablecoins under their regulators’ oversight, while non-banks can issue under a state licensing regime that meets federal standards. This dual approach – essentially giving a thumbs-up to both banks and fintechs – could rapidly “crowd in” new entrants. The result? A much bigger stablecoin ecosystem, and correspondingly, a surge in the volume of Treasurys that ecosystem must hold.

Imagine a world where every major financial institution or tech platform has its own version of a digital dollar. One can envision Apple Dollars for App Store payments, Walmart Coins for retail, or Bank of America stablecoins for clients – all fully backed by Treasurys in segregated reserves. While not all of these will happen, the possibilities are no longer fanciful. The legislative green light would encourage experimentation. And in aggregate, even a few big new issuers could double or triple the stablecoin supply. For the U.S. Treasury, it’s a bit like discovering a new class of investor with a legally mandated appetite for T-bills.

The 3-Month T-Bill: The New Digital Dollar Standard

If stablecoin issuers are poised to become institutionalized buyers of U.S. debt, it’s important to understand what kind of debt they favor. These aren’t the folks buying 10-year notes or 30-year bonds. Stablecoins, by their nature, need reserves that are ultra-safe and liquid. That’s why today’s issuers overwhelmingly hold 3-month Treasury bills, short-term Treasury notes, and overnight Treasury repo agreements. For example, Circle’s USDC reserves are largely invested in the Circle Reserve Fund, an SEC-registered government money market fund managed by BlackRock that holds a mix of short-dated U.S. Treasuries, overnight Treasury repos, and cash. Month after month, Circle discloses that roughly 80% of USDC’s backing is in U.S. Treasurys (through that fund) and about 20% is in cash across a network of banks. This kind of portfolio mirrors what any conservative money market fund would hold – the big difference is that USDC holders don’t earn interest, whereas money market fund investors do. (We’ll come back to that quirk shortly.)

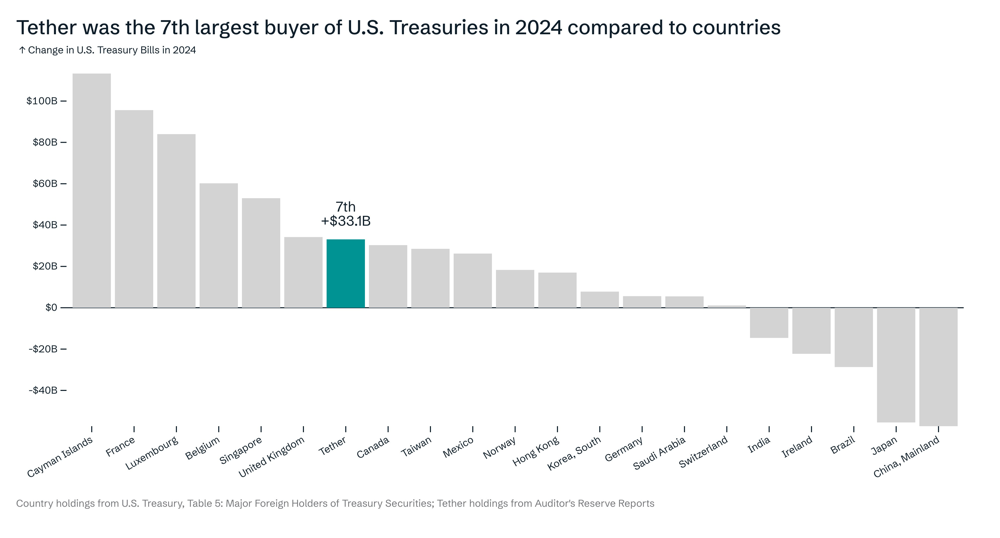

Tether, for its part, has also shifted heavily into short-term Treasurys in the past two years. After facing scrutiny, Tether eliminated riskier holdings (like commercial paper) and now reports the majority of its $80+ billion in reserves are in U.S. T-bills with an average maturity of around 90 days or less. In fact, Tether became such a regular buyer of 3-month bills in 2024 that its net purchases exceeded those of many nations’ central banks. As shown above, Tether added about $33 billion in Treasurys in one year, ranking as the 7th largest net buyer globally. The only bigger net buyers were places like the Cayman Islands, Luxembourg, and a few other financial centers often associated with investment funds. This underscores a key point: stablecoin issuers aren’t just passive holders; they are actively rolling over and reinvesting in new government bills as old ones mature.

By institutionalizing the 100% reserve rule, the GENIUS Act effectively codifies the 3-month T-bill as the gold standard backing for digital dollars. We can expect regulators to strongly encourage (if not explicitly require) that reserves stay in the shortest of short-term instruments to minimize market risk. That means even as stablecoin reserve balances balloon, the money will likely stay concentrated in the front end of the yield curve. The Treasury market could feel this in a few ways:

- A Front-End Yield Anchor: More demand for 3-month and other short-dated T-bills generally pushes their prices up and yields down, all else equal. If stablecoin issuers pour hundreds of billions more into bills, it could exert downward pressure on short-term Treasury yields. In practical terms, that helps the U.S. government borrow more cheaply for very short durations. It’s like having an extra giant money market fund (or several) always soaking up T-bill issuance. As one Treasury market analysis noted, the reserve requirements in the stablecoin bill would provide “an additional and growing source of demand for Treasurys” and specifically drive a “concentration of Treasury holdings at the front-end” of the curve.

- Regular Rollover Buying: Since stablecoin reserves will largely sit in instruments that mature in a matter of weeks or months, issuers must constantly roll them over into new bills. This creates a steady, predictable reinvestment flow. For the Treasury, that could be a stabilizing force – a bit like having a set of repeat customers who show up at every auction for 4-week and 13-week bills. It smooths out demand, potentially reducing volatility in bill auctions. In times of heavy government financing needs (say, raising the debt ceiling and issuing lots of short-term debt), stablecoin issuers could be a welcome sponge to absorb some of the supply.

- Liquidity and “Run” Dynamics: On the flip side, policymakers will keep a wary eye on what happens in a stress scenario. If a major stablecoin experienced a crisis of confidence and holders started redeeming en masse, the issuer would have to start liquidating those T-bills to raise cash. The good news: T-bills are about the most liquid asset on earth, so even a large sale can usually be absorbed. But timing matters – a fire-sale of, say, $10 or $20 billion in Treasurys on a single day could, in theory, cause a momentary dislocation or spike in yields. This is analogous to what happens if a big money market fund faces a run. The GENIUS Act’s authors clearly thought about this, which is why they included provisions for issuers to maintain liquidity buffers and diversify holdings. By having some cash on hand and staggering maturities, a stablecoin issuer in trouble could meet redemptions for a while without dumping all their bonds at once. In the long run, the very requirement of 100% backing is supposed to prevent runs (since users know the money’s there). But in any case, regulators will likely treat large stablecoins as systemically important money-market-like funds that just can’t be allowed to collapse overnight. We may even see the Federal Reserve extend emergency backstop facilities (as it does to traditional finance) if a stablecoin wobble ever threatened broader market stability.

On balance, though, the day-to-day implication is that stablecoins become a permanent fixture of demand in short-term funding markets. They join banks, money market funds, and foreign central banks as key buyers of U.S. T-bills. And unlike some other buyers, stablecoin issuers aren’t yield-sensitive in the usual way – they have to buy, regardless of whether the 3-month yield is 5% or 0.5%, because their mandate is simply to park dollar reserves safely. This quasi price-insensitive demand can be a double-edged sword: it’s great for keeping government funding costs low during normal times, but if something causes stablecoin growth to stall or reverse, that demand could evaporate. Still, with the global appetite for digital dollars seemingly growing, few in Washington are complaining. As Senator Hagerty put it, the benefits of stablecoin innovation – from payments efficiency to “driving demand for U.S. Treasuries” – are simply “immense”.

Money Market Fund or Digital Dollar? The Mechanics of Reserve Management

There’s an interesting wrinkle in how stablecoin reserves are managed. Some issuers hold Treasurys directly, building their own mini-portfolio of bills. Others, like Circle, invest reserves into a money market fund (MMF) that itself holds Treasurys. The GENIUS Act contemplates these arrangements and actually provides a carve-out in regulatory classification: a stablecoin issuer complying with the law will not be treated as an investment company (i.e., it won’t be regulated like a mutual fund). This is important, because without that exemption, a company pooling tens of billions of dollars to invest in securities might be deemed a money market fund and come under the stricter rules of the Investment Company Act. Congress wisely sidestepped that by defining “payment stablecoins” as a new category, distinct from securities or commodities. Essentially, they’re saying: as long as you play by the stablecoin rules – full backing, no funny business – you’re not going to get tangled up by the SEC as a mutual fund or by the CFTC as a commodity pool.

What does that mean in practice? It frees stablecoin issuers to use structures like government MMFs for their reserves without worrying that the stablecoin itself will be treated as a fund share. Circle’s partnership with BlackRock on the Circle Reserve Fund is a case in point. That fund is a low-risk government-only fund, and Circle owns 100% of its equity (meaning USDC’s reserves are essentially the sole investor in the fund). Every USDC in circulation is matched by a share in that fund or cash in bank – a model that has so far kept USDC very stable. Other issuers might follow suit by outsourcing reserve management to professional fund managers. It’s efficient: rather than each stablecoin treasury team trying to pick which bills to buy each week, they can entrust the money to an established MMF that offers daily liquidity. The trade-off is a small management fee, but given the yields on T-bills lately (around 5% in 2023–2024), there’s plenty of interest income to go around.

Speaking of interest income – one somewhat hidden dynamic is who earns the yield on those massive reserve holdings. In today’s stablecoins, it’s typically the issuer (and sometimes their partners). Unlike a bank deposit or a money market fund, stablecoins generally don’t pay holders any interest. If you hold 1,000 USDC, it’s always worth $1,000, and you don’t get more for holding it. Meanwhile, the issuer has invested that $1,000 into T-bills earning, say, 5%. That yield funds the stablecoin business and, in some cases, is shared with strategic partners (for example, Circle shares some USDC revenue with Coinbase, and Paxos shares some with PayPal for PYUSD). Under the GENIUS Act, this model can continue, but there’s a catch: issuers must be careful not to offer anything that looks like an investment return to stablecoin holders, lest the token be deemed a security. Lawmakers explicitly warned that if an issuer “tries to pay interest” on a stablecoin, it might fall outside the protected regulatory category. So, don’t expect interest-bearing stablecoins (at least not straightforward ones) unless Congress later amends the rules. This could actually help keep banks happier – stablecoins won’t be able to openly compete by offering yield, so they won’t instantly suck away all interest-sensitive deposits. Nonetheless, the high yields earned on reserves in the current rate environment have made stablecoin issuers very profitable, and that will likely attract more entrants. It’s been observed that stablecoins are almost like “money market funds in disguise,” but ones where the sponsors keep the yield rather than passing it to holders. If competition heats up, market forces might push issuers to improve terms for users (perhaps via lower fees or other perks since they can’t offer interest). Either way, as stablecoins scale, the dollars flowing into MMFs or directly into T-bills will scale in tandem – a significant boon for U.S. debt markets.

Crowding In Wall Street and Silicon Valley

Regulatory clarity tends to act like a magnet for big players. In the stablecoin realm, that means both Wall Street banks and Silicon Valley tech firms could jump in once the rules of the road are set. The GENIUS Act’s approach to issuer eligibility is notably open-armed: insured banks, state-licensed trust companies, money transmitters, and even big tech companies can all issue stablecoins if they meet the requirements. Unlike some earlier proposals, there’s no blanket ban keeping the Googles or Amazons out – a conscious decision by Congress to encourage innovation (a stark change from the days when Facebook’s Libra was practically run out of town). This means we might see a diversity of new stablecoins designed for different niches. For example:

- Fintech-issued stablecoins: PayPal has already launched PYUSD (in partnership with Paxos) to integrate digital dollars into its payment network. If the law solidifies, PayPal could aggressively grow PYUSD usage for e-commerce and remittances. Other fintech apps (Square’s Cash App, Stripe, etc.) might issue or support their own tokens to facilitate instant payments. Imagine Venmo or Robinhood dollar tokens that let users seamlessly move money on-chain but within a regulated framework.

- Bank-issued stablecoins: Some large U.S. banks have dabbled with blockchain for internal transfers (e.g. JPMorgan’s JPM Coin), but few have issued a public stablecoin due to regulatory uncertainty. The Act could change that. A bank could offer a token redeemable at the bank, effectively a digital deposit. Community and regional banks might even band together to offer a common stablecoin for their customers, as a way to stay relevant in a tokenized economy. This could keep deposit funding within the banking system (albeit in a transformed way) and provide competition to non-bank coins. Banks already hold tons of Treasurys on their balance sheets; issuing a stablecoin would simply earmark some of those assets as backing for tokenized deposits, potentially expanding their holdings further if the coin gets popular.

- Tech and Corporate stablecoins: It’s not just finance companies. Think of a retailer like Walmart enabling a digital dollar token for shoppers, or a telecom company using stablecoins for mobile money transfers. With clear law, even non-financial brands could dip their toes in – though they’d have to build up or outsource a lot of financial compliance capability. One could envision consortiums where a tech firm provides the user interface and distribution, while a financial partner manages the reserves and regulatory compliance.

Every new entrant and every use case could add incremental demand for Treasurys. A large tech firm’s stablecoin with, say, $10 billion in circulation would mean an extra $10B parked in T-bills somewhere in the financial system. Multiply that across several initiatives and the numbers climb. Indeed, proponents of the law see stablecoins not only as a payments innovation but as a strategic asset for the country. By creating a welcoming environment, they hope to “keep crypto companies and jobs onshore” and harness stablecoins as an extension of U.S. economic influence.

There’s a subtle geopolitical angle here: if U.S. firms dominate global stablecoins, that strengthens the international role of the dollar. In the early 2020s, much of stablecoin adoption happened outside the U.S. (with Tether, an offshore entity, serving markets in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East where dollars are in demand). A regulated U.S. stablecoin framework could bring a lot of that activity under the U.S. regulatory umbrella and encourage new U.S.-based issuers to compete. “We want that value creation to happen in the United States rather than giving it away to other countries,” as David Sacks emphasized when discussing why a clear framework is needed. The law would effectively crowd in legitimate players while crowding out unregulated or risky ones over time. If a foreign stablecoin issuer (like Tether) chose not to comply, they would eventually find themselves locked out of U.S. markets – and perhaps facing diminished trust if U.S.-regulated alternatives proliferate. That’s not to say Tether will disappear (it may continue serving markets that are less concerned with U.S. oversight), but its dominance could wane if, say, a coalition of U.S. firms offers a trusted, regulated dollar token that’s broadly accessible.

Dollar Dominance, Digital Currencies, and Geopolitics

At the heart of this discussion is a fascinating shift in how the U.S. dollar projects power. Stablecoins are, in a sense, the private-sector answer to central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). While China, Europe, and others work on official CBDCs, the U.S. has been relatively slow on a digital dollar from the Fed. Instead, American innovation spurred dollar-backed tokens from companies – and those tokens exploded in use globally. Policymakers are now essentially leveraging that trend to reinforce the dollar’s role. If the GENIUS Act passes, the U.S. would be saying: we’re going to supervise these digital dollars, make them safe, and let them flourish under our rules.

Several lawmakers have linked stablecoin regulation directly with preserving the dollar’s preeminence. Senator Lummis and Senator Gillibrand both used almost identical language about maintaining U.S. dollar dominance as a key rationale for the bill. The subtext is clear: In a world where competitors (like a digital yuan or the euro’s contemplated digital euro) might challenge the dollar in the digital realm, America’s best weapon could be the ingenuity of its private sector – harnessed by prudent regulation. A well-regulated U.S. stablecoin could become the de facto digital dollar globally, reaching places the Federal Reserve can’t easily touch. Already, dollar stablecoins circulate in markets from Buenos Aires to Istanbul to Nairobi, where local currencies are volatile and accessing U.S. banks is difficult. These tokens have been described as a new form of “eurodollar” – a 21st-century version of offshore dollar accounts that drove global finance in the late 20th century. The difference is, stablecoins move at internet speed, 24/7, and can be held by anyone with a smartphone. That’s powerful. As long as they are redeemable 1:1 for real dollars, they effectively extend the reach of the Federal Reserve’s monetary power (every stablecoin in circulation is, after all, backed by U.S. assets and ultimately U.S. dollars).

There are, of course, national security and monetary policy considerations. U.S. regulators will insist on strict AML/KYC compliance for regulated stablecoins – no one wants these becoming a haven for illicit finance. The GENIUS Act explicitly requires issuers to follow all anti-money-laundering and sanctions rules, which is critical for getting law enforcement and Treasury Department on board. Part of the reason policymakers might prefer well-regulated private stablecoins to something like an uncontrolled Tether is precisely the ability to monitor and enforce financial laws on the former. If stablecoins truly go mainstream, the government will likely gain better visibility into global dollar flows (via the regulated entities) than it has with opaque offshore dollar movements today.

From a monetary policy perspective, stablecoins thus far haven’t been large enough to notably affect things like money supply or interest rates beyond the micro scale of crypto markets. However, if we imagine a future with $2 trillion in stablecoins, the Fed will treat that as part of the broader money environment. Interestingly, a fully reserved stablecoin doesn’t create net new money in the economy – it transforms bank deposits or cash into a digital token, and the backing assets sit in Treasurys or at the Fed (if cash in a bank is ultimately held as reserves at the Fed). So the net impact on U.S. money supply might be neutral. But there is a scenario where stablecoins bring in new money from abroad: for example, a person in a country with capital controls might sell local assets to buy USDC, effectively pulling liquidity into the dollar system. The Treasury’s advisory committee noted that the attractiveness of USD stablecoins could “drive currently non-USD liquidity holdings into USD” – in other words, foreign money seeking the stability of dollars could flow into these tokens. That would reinforce dollar hegemony, but it might also complicate other countries’ monetary policies (some emerging markets already worry about “dollarization” via crypto). The IMF has voiced concerns about stablecoins eroding monetary sovereignty in countries with weak currencies.

Finally, there’s the interplay with a potential Fed-issued digital dollar. Some argue that if private stablecoins do the job, the Fed may not need to roll out a retail CBDC at all. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has commented that he’s not against stablecoins if they are properly regulated; he just wants clear guardrails since, in his view, stablecoins “are like money market funds, they need appropriate regulation.” Now that Congress is delivering those guardrails, the Fed might focus on improving wholesale settlement systems (like the new FedNow instant payment system) and leave retail innovation to the market. On the other hand, if the Fed ever did issue its own digital dollar, it would step into direct competition with private stablecoins – offering the safest possible digital money (a central bank liability) versus very safe but not zero-risk private tokens. That day seems distant, and politically a Fed CBDC faces headwinds. In the meantime, the U.S. is effectively outsourcing digital dollar innovation to the private sector, with stablecoins as the vehicle, and using laws like the GENIUS Act to ensure that vehicle stays on the road and under supervision.

Conclusion: An Unlikely Symbiosis of Crypto and U.S. Debt

Not long ago, it would have been hard to imagine crypto entrepreneurs playing a significant role in financing the U.S. government’s deficit. Yet here we are: stablecoin issuers have become a silent force in the Treasury market, and Washington is poised to solidify that symbiosis. The GENIUS Act, by institutionalizing stablecoin reserve requirements, doesn’t just tame a Wild West corner of finance – it also taps into it. It’s a recognition that the humble stablecoin, a product born on the fringes of crypto trading, has matured into something with profound macroeconomic relevance. These digital dollars could help ensure there’s always a strong bid for America’s debt, even as traditional buyers ebb and flow. They could reinforce the dollar’s dominance by weaving it into the internet’s infrastructure, token by token, transaction by transaction.

Of course, this comes with challenges and unknowns. Regulators will have to remain vigilant that stablecoins don’t grow unwieldy or introduce new risks. In a future crisis, will stablecoin holders behave differently than other money market investors? Will a tech glitch or cyber attack on a major stablecoin reverberate through financial markets? These questions keep officials up at night, which is why getting the regulatory framework right is so essential. The GENIUS Act is a big step in that direction – creating rules to make stablecoins boring in the best possible way (reliable, fully backed, transparent) while unleashing their innovative potential for payments and beyond.

As this new chapter unfolds, we’ll be watching an intriguing experiment: Can a marriage between crypto and the U.S. Treasury benefit both? On one side, we have the Treasury, which, perennially hungry for buyers, may find a growing ally in stablecoin issuers to help absorb its never-ending stream of bills. On the other side, we have the stablecoin industry, which needs the credibility and safety that only the deepest government debt market can provide. It’s a mutually beneficial arrangement – stablecoins bolster their trust by leaning on Treasurys, and Treasurys get incremental demand by leaning on stablecoins.

In the long run, a successfully regulated stablecoin sector could weave the U.S. dollar even more tightly into the fabric of global digital commerce. It’s a development full of irony and promise: an innovation that started as an attempt to bypass traditional finance might end up buttressing the reigning financial order. As Senator Hagerty and his colleagues push the GENIUS Act forward, the message is clear – they see stablecoins as a strategic asset for U.S. interests. “The potential benefits of strong stablecoin innovation are immense,” Hagerty said, and he wasn’t just referring to tech efficiency. Part of that potential, now coming into focus, is to channel the world’s appetite for digital dollars into the very real funding needs of the United States. In an age of mounting deficits and global currency competition, that might just prove to be a stroke of genius.